SO were mine eyes inebriate with view

Of the vast multitude, whom various wounds

Disfigur'd, that they long'd to stay and weep.

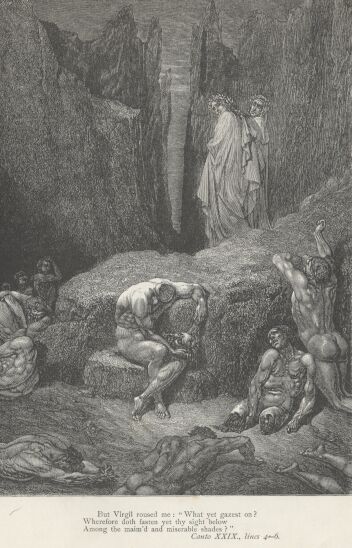

But Virgil rous'd me: "What yet gazest on?

Wherefore doth fasten yet thy sight below

Among the maim'd and miserable shades?

Thou hast not shewn in any chasm beside

This weakness. Know, if thou wouldst number them

That two and twenty miles the valley winds

Its circuit, and already is the moon

Beneath our feet: the time permitted now

Is short, and more not seen remains to see."

"If thou," I straight replied, "hadst weigh'd the cause

For which I look'd, thou hadst perchance excus'd

The tarrying still." My leader part pursu'd

His way, the while I follow'd, answering him,

And adding thus: "Within that cave I deem,

Whereon so fixedly I held my ken,

There is a spirit dwells, one of my blood,

Wailing the crime that costs him now so dear."

Then spake my master: "Let thy soul no more

Afflict itself for him. Direct elsewhere

Its thought, and leave him. At the bridge's foot

I mark'd how he did point with menacing look

At thee, and heard him by the others nam'd

Geri of Bello. Thou so wholly then

Wert busied with his spirit, who once rul'd

The towers of Hautefort, that thou lookedst not

That way, ere he was gone."—"O guide belov'd!

His violent death yet unaveng'd," said I,

"By any, who are partners in his shame,

Made him contemptuous: therefore, as I think,

He pass'd me speechless by; and doing so

Hath made me more compassionate his fate."

So we discours'd to where the rock first show'd

The other valley, had more light been there,

E'en to the lowest depth. Soon as we came

O'er the last cloister in the dismal rounds

Of Malebolge, and the brotherhood

Were to our view expos'd, then many a dart

Of sore lament assail'd me, headed all

With points of thrilling pity, that I clos'd

Both ears against the volley with mine hands.

As were the torment, if each lazar-house

Of Valdichiana, in the sultry time

'Twixt July and September, with the isle

Sardinia and Maremma's pestilent fen,

Had heap'd their maladies all in one foss

Together; such was here the torment: dire

The stench, as issuing steams from fester'd limbs.

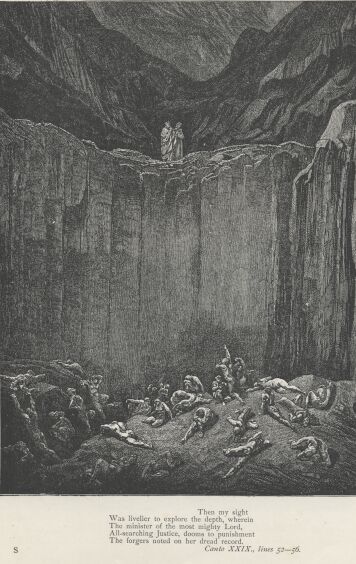

We on the utmost shore of the long rock

Descended still to leftward. Then my sight

Was livelier to explore the depth, wherein

The minister of the most mighty Lord,

All-searching Justice, dooms to punishment

The forgers noted on her dread record.

More rueful was it not methinks to see

The nation in Aegina droop, what time

Each living thing, e'en to the little worm,

All fell, so full of malice was the air

(And afterward, as bards of yore have told,

The ancient people were restor'd anew

From seed of emmets) than was here to see

The spirits, that languish'd through the murky vale

Up-pil'd on many a stack. Confus'd they lay,

One o'er the belly, o'er the shoulders one

Roll'd of another; sideling crawl'd a third

Along the dismal pathway. Step by step

We journey'd on, in silence looking round

And list'ning those diseas'd, who strove in vain

To lift their forms. Then two I mark'd, that sat

Propp'd 'gainst each other, as two brazen pans

Set to retain the heat. From head to foot,

A tetter bark'd them round. Nor saw I e'er

Groom currying so fast, for whom his lord

Impatient waited, or himself perchance

Tir'd with long watching, as of these each one

Plied quickly his keen nails, through furiousness

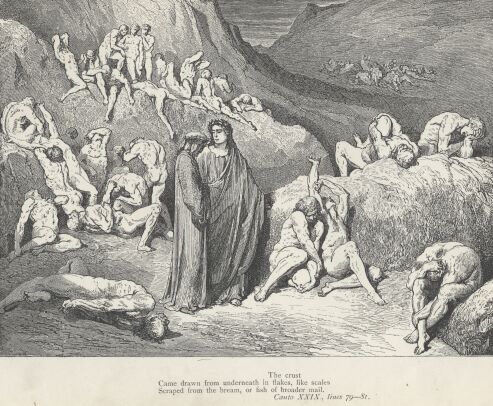

Of ne'er abated pruriency. The crust

Came drawn from underneath in flakes, like scales

Scrap'd from the bream or fish of broader mail.

"O thou, who with thy fingers rendest off

Thy coat of proof," thus spake my guide to one,

"And sometimes makest tearing pincers of them,

Tell me if any born of Latian land

Be among these within: so may thy nails

Serve thee for everlasting to this toil."

"Both are of Latium," weeping he replied,

"Whom tortur'd thus thou seest: but who art thou

That hast inquir'd of us?" To whom my guide:

"One that descend with this man, who yet lives,

From rock to rock, and show him hell's abyss."

Then started they asunder, and each turn'd

Trembling toward us, with the rest, whose ear

Those words redounding struck. To me my liege

Address'd him: "Speak to them whate'er thou list."

And I therewith began: "So may no time

Filch your remembrance from the thoughts of men

In th' upper world, but after many suns

Survive it, as ye tell me, who ye are,

And of what race ye come. Your punishment,

Unseemly and disgustful in its kind,

Deter you not from opening thus much to me."

"Arezzo was my dwelling," answer'd one,

"And me Albero of Sienna brought

To die by fire; but that, for which I died,

Leads me not here. True is in sport I told him,

That I had learn'd to wing my flight in air.

And he admiring much, as he was void

Of wisdom, will'd me to declare to him

The secret of mine art: and only hence,

Because I made him not a Daedalus,

Prevail'd on one suppos'd his sire to burn me.

But Minos to this chasm last of the ten,

For that I practis'd alchemy on earth,

Has doom'd me. Him no subterfuge eludes."

Then to the bard I spake: "Was ever race

Light as Sienna's? Sure not France herself

Can show a tribe so frivolous and vain."

The other leprous spirit heard my words,

And thus return'd: "Be Stricca from this charge

Exempted, he who knew so temp'rately

To lay out fortune's gifts; and Niccolo

Who first the spice's costly luxury

Discover'd in that garden, where such seed

Roots deepest in the soil: and be that troop

Exempted, with whom Caccia of Asciano

Lavish'd his vineyards and wide-spreading woods,

And his rare wisdom Abbagliato show'd

A spectacle for all. That thou mayst know

Who seconds thee against the Siennese

Thus gladly, bend this way thy sharpen'd sight,

That well my face may answer to thy ken;

So shalt thou see I am Capocchio's ghost,

Who forg'd transmuted metals by the power

Of alchemy; and if I scan thee right,

Thus needs must well remember how I aped

Creative nature by my subtle art."

WHAT time resentment burn'd in Juno's breast

For Semele against the Theban blood,

As more than once in dire mischance was rued,

Such fatal frenzy seiz'd on Athamas,

That he his spouse beholding with a babe

Laden on either arm, "Spread out," he cried,

"The meshes, that I take the lioness

And the young lions at the pass:" then forth

Stretch'd he his merciless talons, grasping one,

One helpless innocent, Learchus nam'd,

Whom swinging down he dash'd upon a rock,

And with her other burden self-destroy'd

The hapless mother plung'd: and when the pride

Of all-presuming Troy fell from its height,

By fortune overwhelm'd, and the old king

With his realm perish'd, then did Hecuba,

A wretch forlorn and captive, when she saw

Polyxena first slaughter'd, and her son,

Her Polydorus, on the wild sea-beach

Next met the mourner's view, then reft of sense

Did she run barking even as a dog;

Such mighty power had grief to wrench her soul.

Bet ne'er the Furies or of Thebes or Troy

With such fell cruelty were seen, their goads

Infixing in the limbs of man or beast,

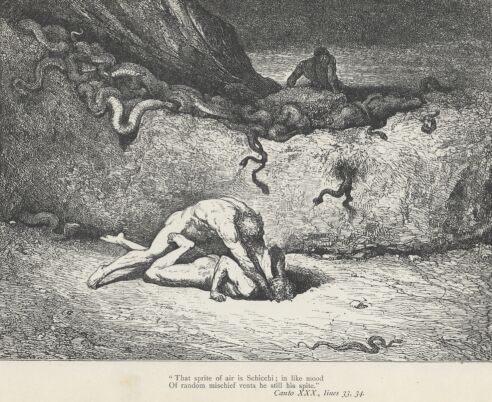

As now two pale and naked ghost I saw

That gnarling wildly scamper'd, like the swine

Excluded from his stye. One reach'd Capocchio,

And in the neck-joint sticking deep his fangs,

Dragg'd him, that o'er the solid pavement rubb'd

His belly stretch'd out prone. The other shape,

He of Arezzo, there left trembling, spake;

"That sprite of air is Schicchi; in like mood

Of random mischief vent he still his spite."

To whom I answ'ring: "Oh! as thou dost hope,

The other may not flesh its jaws on thee,

Be patient to inform us, who it is,

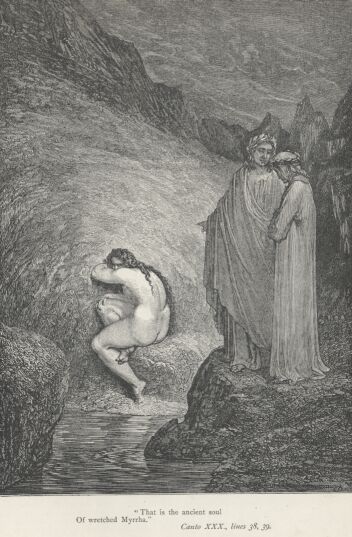

Ere it speed hence."—"That is the ancient soul

Of wretched Myrrha," he replied, "who burn'd

With most unholy flame for her own sire,

"And a false shape assuming, so perform'd

The deed of sin; e'en as the other there,

That onward passes, dar'd to counterfeit

Donati's features, to feign'd testament

The seal affixing, that himself might gain,

For his own share, the lady of the herd."

When vanish'd the two furious shades, on whom

Mine eye was held, I turn'd it back to view

The other cursed spirits. One I saw

In fashion like a lute, had but the groin

Been sever'd, where it meets the forked part.

Swoln dropsy, disproportioning the limbs

With ill-converted moisture, that the paunch

Suits not the visage, open'd wide his lips

Gasping as in the hectic man for drought,

One towards the chin, the other upward curl'd.

"O ye, who in this world of misery,

Wherefore I know not, are exempt from pain,"

Thus he began, "attentively regard

Adamo's woe. When living, full supply

Ne'er lack'd me of what most I coveted;

One drop of water now, alas! I crave.

The rills, that glitter down the grassy slopes

Of Casentino, making fresh and soft

The banks whereby they glide to Arno's stream,

Stand ever in my view; and not in vain;

For more the pictur'd semblance dries me up,

Much more than the disease, which makes the flesh

Desert these shrivel'd cheeks. So from the place,

Where I transgress'd, stern justice urging me,

Takes means to quicken more my lab'ring sighs.

There is Romena, where I falsified

The metal with the Baptist's form imprest,

For which on earth I left my body burnt.

But if I here might see the sorrowing soul

Of Guido, Alessandro, or their brother,

For Branda's limpid spring I would not change

The welcome sight. One is e'en now within,

If truly the mad spirits tell, that round

Are wand'ring. But wherein besteads me that?

My limbs are fetter'd. Were I but so light,

That I each hundred years might move one inch,

I had set forth already on this path,

Seeking him out amidst the shapeless crew,

Although eleven miles it wind, not more

Than half of one across. They brought me down

Among this tribe; induc'd by them I stamp'd

The florens with three carats of alloy."

"Who are that abject pair," I next inquir'd,

"That closely bounding thee upon thy right

Lie smoking, like a band in winter steep'd

In the chill stream?"—"When to this gulf I dropt,"

He answer'd, "here I found them; since that hour

They have not turn'd, nor ever shall, I ween,

Till time hath run his course. One is that dame

The false accuser of the Hebrew youth;

Sinon the other, that false Greek from Troy.

Sharp fever drains the reeky moistness out,

In such a cloud upsteam'd." When that he heard,

One, gall'd perchance to be so darkly nam'd,

With clench'd hand smote him on the braced paunch,

That like a drum resounded: but forthwith

Adamo smote him on the face, the blow

Returning with his arm, that seem'd as hard.

"Though my o'erweighty limbs have ta'en from me

The power to move," said he, "I have an arm

At liberty for such employ." To whom

Was answer'd: "When thou wentest to the fire,

Thou hadst it not so ready at command,

Then readier when it coin'd th' impostor gold."

And thus the dropsied: "Ay, now speak'st thou true.

But there thou gav'st not such true testimony,

When thou wast question'd of the truth, at Troy."

"If I spake false, thou falsely stamp'dst the coin,"

Said Sinon; "I am here but for one fault,

And thou for more than any imp beside."

"Remember," he replied, "O perjur'd one,

The horse remember, that did teem with death,

And all the world be witness to thy guilt."

"To thine," return'd the Greek, "witness the thirst

Whence thy tongue cracks, witness the fluid mound,

Rear'd by thy belly up before thine eyes,

A mass corrupt." To whom the coiner thus:

"Thy mouth gapes wide as ever to let pass

Its evil saying. Me if thirst assails,

Yet I am stuff'd with moisture. Thou art parch'd,

Pains rack thy head, no urging would'st thou need

To make thee lap Narcissus' mirror up."

I was all fix'd to listen, when my guide

Admonish'd: "Now beware: a little more.

And I do quarrel with thee." I perceiv'd

How angrily he spake, and towards him turn'd

With shame so poignant, as remember'd yet

Confounds me. As a man that dreams of harm

Befall'n him, dreaming wishes it a dream,

And that which is, desires as if it were not,

Such then was I, who wanting power to speak

Wish'd to excuse myself, and all the while

Excus'd me, though unweeting that I did.

"More grievous fault than thine has been, less shame,"

My master cried, "might expiate. Therefore cast

All sorrow from thy soul; and if again

Chance bring thee, where like conference is held,

Think I am ever at thy side. To hear

Such wrangling is a joy for vulgar minds."

THE very tongue, whose keen reproof before

Had wounded me, that either cheek was stain'd,

Now minister'd my cure. So have I heard,

Achilles and his father's javelin caus'd

Pain first, and then the boon of health restor'd.

Turning our back upon the vale of woe,

W cross'd th' encircled mound in silence. There

Was twilight dim, that far long the gloom

Mine eye advanc'd not: but I heard a horn

Sounded aloud. The peal it blew had made

The thunder feeble. Following its course

The adverse way, my strained eyes were bent

On that one spot. So terrible a blast

Orlando blew not, when that dismal rout

O'erthrew the host of Charlemagne, and quench'd

His saintly warfare. Thitherward not long

My head was rais'd, when many lofty towers

Methought I spied. "Master," said I, "what land

Is this?" He answer'd straight: "Too long a space

Of intervening darkness has thine eye

To traverse: thou hast therefore widely err'd

In thy imagining. Thither arriv'd

Thou well shalt see, how distance can delude

The sense. A little therefore urge thee on."

Then tenderly he caught me by the hand;

"Yet know," said he, "ere farther we advance,

That it less strange may seem, these are not towers,

But giants. In the pit they stand immers'd,

Each from his navel downward, round the bank."

As when a fog disperseth gradually,

Our vision traces what the mist involves

Condens'd in air; so piercing through the gross

And gloomy atmosphere, as more and more

We near'd toward the brink, mine error fled,

And fear came o'er me. As with circling round

Of turrets, Montereggion crowns his walls,

E'en thus the shore, encompassing th' abyss,

Was turreted with giants, half their length

Uprearing, horrible, whom Jove from heav'n

Yet threatens, when his mutt'ring thunder rolls.

Of one already I descried the face,

Shoulders, and breast, and of the belly huge

Great part, and both arms down along his ribs.

All-teeming nature, when her plastic hand

Left framing of these monsters, did display

Past doubt her wisdom, taking from mad War

Such slaves to do his bidding; and if she

Repent her not of th' elephant and whale,

Who ponders well confesses her therein

Wiser and more discreet; for when brute force

And evil will are back'd with subtlety,

Resistance none avails. His visage seem'd

In length and bulk, as doth the pine, that tops

Saint Peter's Roman fane; and th' other bones

Of like proportion, so that from above

The bank, which girdled him below, such height

Arose his stature, that three Friezelanders

Had striv'n in vain to reach but to his hair.

Full thirty ample palms was he expos'd

Downward from whence a man his garments loops.

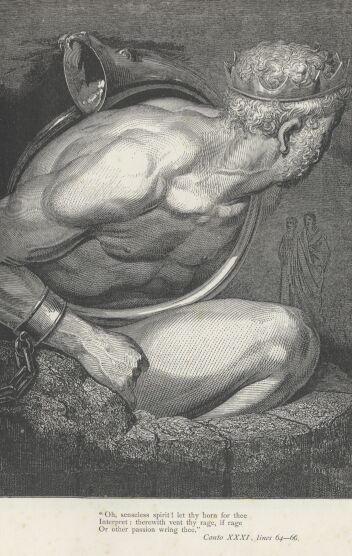

"Raphel bai ameth sabi almi,"

So shouted his fierce lips, which sweeter hymns

Became not; and my guide address'd him thus:

"O senseless spirit! let thy horn for thee

Interpret: therewith vent thy rage, if rage

Or other passion wring thee. Search thy neck,

There shalt thou find the belt that binds it on.

Wild spirit! lo, upon thy mighty breast

Where hangs the baldrick!" Then to me he spake:

"He doth accuse himself. Nimrod is this,

Through whose ill counsel in the world no more

One tongue prevails. But pass we on, nor waste

Our words; for so each language is to him,

As his to others, understood by none."

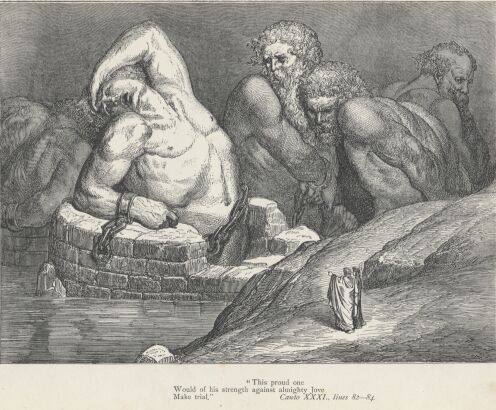

Then to the leftward turning sped we forth,

And at a sling's throw found another shade

Far fiercer and more huge. I cannot say

What master hand had girt him; but he held

Behind the right arm fetter'd, and before

The other with a chain, that fasten'd him

From the neck down, and five times round his form

Apparent met the wreathed links. "This proud one

Would of his strength against almighty Jove

Make trial," said my guide; "whence he is thus

Requited: Ephialtes him they call.

"Great was his prowess, when the giants brought

Fear on the gods: those arms, which then he piled,

Now moves he never." Forthwith I return'd:

"Fain would I, if 't were possible, mine eyes

Of Briareus immeasurable gain'd

Experience next." He answer'd: "Thou shalt see

Not far from hence Antaeus, who both speaks

And is unfetter'd, who shall place us there

Where guilt is at its depth. Far onward stands

Whom thou wouldst fain behold, in chains, and made

Like to this spirit, save that in his looks

More fell he seems." By violent earthquake rock'd

Ne'er shook a tow'r, so reeling to its base,

As Ephialtes. More than ever then

I dreaded death, nor than the terror more

Had needed, if I had not seen the cords

That held him fast. We, straightway journeying on,

Came to Antaeus, who five ells complete

Without the head, forth issued from the cave.

"O thou, who in the fortunate vale, that made

Great Scipio heir of glory, when his sword

Drove back the troop of Hannibal in flight,

Who thence of old didst carry for thy spoil

An hundred lions; and if thou hadst fought

In the high conflict on thy brethren's side,

Seems as men yet believ'd, that through thine arm

The sons of earth had conquer'd, now vouchsafe

To place us down beneath, where numbing cold

Locks up Cocytus. Force not that we crave

Or Tityus' help or Typhon's. Here is one

Can give what in this realm ye covet. Stoop

Therefore, nor scornfully distort thy lip.

He in the upper world can yet bestow

Renown on thee, for he doth live, and looks

For life yet longer, if before the time

Grace call him not unto herself." Thus spake

The teacher. He in haste forth stretch'd his hands,

And caught my guide. Alcides whilom felt

That grapple straighten'd score. Soon as my guide

Had felt it, he bespake me thus: "This way

That I may clasp thee;" then so caught me up,

That we were both one burden. As appears

The tower of Carisenda, from beneath

Where it doth lean, if chance a passing cloud

So sail across, that opposite it hangs,

Such then Antaeus seem'd, as at mine ease

I mark'd him stooping. I were fain at times

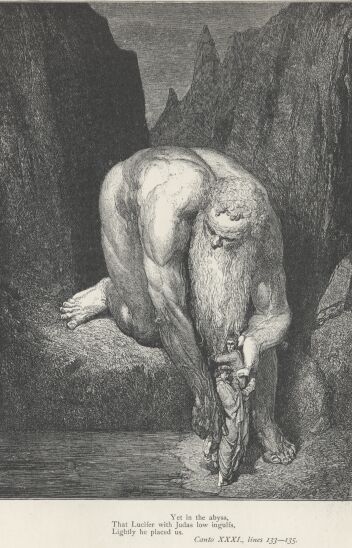

T' have pass'd another way. Yet in th' abyss,

That Lucifer with Judas low ingulfs,

lightly he plac'd us; nor there leaning stay'd,

But rose as in a bark the stately mast.